English Corner

http://repository.upenn.edu/ljsproceedings/vol2/iss1/7/

Conference materials

http://repository.upenn.edu/ljsproceedings/vol2/iss1/

Conference materials

http://repository.upenn.edu/ljsproceedings/vol2/iss1/

KlausGraf - am Dienstag, 13. April 2010, 01:38 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen

KlausGraf - am Montag, 12. April 2010, 23:35 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen

"Rwanda has insisted that all archives of the 1994 genocide should be hosted by Kigali, including that of the Arusha based International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR).

Making his opening remarks at the symposium on genocide against Tutsis on Monday, Rwanda's Minister for Sports and Culture Joseph Habineza said all efforts should be made to preserve whatever was available after the genocide.

‘'I heard that ICTR archives could be preserved either in Europe or Tanzania. Why? They are our archives and we want them here [Rwanda],'' the Minister emphasized before the participants at the Serena Hotel.

The United Nations Security Council is still debating on where to keep the ICTR archives as the UN court winds up all first instance trials later this year. Three countries are considered as front-runners to host the ICTR archives namely Tanzania, Rwanda and Kenya.

The minister also informed the participants that the government would soon conclude discussions with experts from the United Kingdom on how to preserve the remains of various genocide memorial museums in the country.

Other items earmarked to be preserved include tools used for killings, gacaca (Rwandan semi traditional courts) records and images, books, movies, documentaries and memorial sites.

Professor Laurent Nkusi, President of Rwanda Scientific Commission, when presenting a paper titled ‘' Keeping Memory and Documentation'' stressed that keeping memory would facilitate reconciliation process and also serve as a lesson to the Rwandans and the world at large.

The three-day symposium organized by the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide (CNLG), is part of the activities to mark the 16th anniversary of genocide."

Link

Making his opening remarks at the symposium on genocide against Tutsis on Monday, Rwanda's Minister for Sports and Culture Joseph Habineza said all efforts should be made to preserve whatever was available after the genocide.

‘'I heard that ICTR archives could be preserved either in Europe or Tanzania. Why? They are our archives and we want them here [Rwanda],'' the Minister emphasized before the participants at the Serena Hotel.

The United Nations Security Council is still debating on where to keep the ICTR archives as the UN court winds up all first instance trials later this year. Three countries are considered as front-runners to host the ICTR archives namely Tanzania, Rwanda and Kenya.

The minister also informed the participants that the government would soon conclude discussions with experts from the United Kingdom on how to preserve the remains of various genocide memorial museums in the country.

Other items earmarked to be preserved include tools used for killings, gacaca (Rwandan semi traditional courts) records and images, books, movies, documentaries and memorial sites.

Professor Laurent Nkusi, President of Rwanda Scientific Commission, when presenting a paper titled ‘' Keeping Memory and Documentation'' stressed that keeping memory would facilitate reconciliation process and also serve as a lesson to the Rwandans and the world at large.

The three-day symposium organized by the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide (CNLG), is part of the activities to mark the 16th anniversary of genocide."

Link

Wolf Thomas - am Sonntag, 11. April 2010, 17:58 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen

Fintan O´Toole wrote in the Irish Times: "CULTURE SHOCK: The chaos in public policy concerning archives in general, and health records in particular, demonstrates the Government's lack of concern for people who records are - by law - in its care

IN MAY 2008, a woman searching for her cat near Glounthaune, outside Cork city, came across hundreds of intact files at an old landfill site. They were records from the 1970s and 1980s from St Finbarr’s and Cork University hospitals. The HSE said it had no idea how they got there. It was not the first time that dumped medical files had been found in Cork, but it was a particularly dramatic illustration of the effects of the chaos in public policy concerning archives in general and health records in particular.

Anyone with an interest in Irish history, at either a local or a national level, is probably aware of the crisis in our archives. The National Archives are almost literally full and forced to move material into unsuitable off-site storage in order to make way for the new records that have to be taken in every year. There is no coherent policy on the retention of the digital documents that now make up the bulk of official records. The Government has not bothered to re-appoint the statutory National Archives Advisory Council since the last term of office ended in November 2007 – a breach of the law that suggests a degree of outright contempt. Official policy is dominated by a hare-brained notion of merging the National Archives and the National Library.

It is easy to dismiss all of this as a matter of concern only to professional historians. It actually goes to the heart of something much larger – our collective notions of who we are. What is at stake is our ability to define our own reality. We’ve learned in the most painful way, principally from the Ryan report into the industrial school system, that the successful occlusion of some of the darkest aspects of Irish life allows us to lie about ourselves. Those lies are toxic.

One of the things that happens when the preservation of records is neglected is a strengthening of the tendency for history to be written by – or at least from the perspective of – the winners. The records of government and high diplomacy will probably survive. What get lost are the vestiges of the lives of the ordinary, the anonymous, the vulnerable. The stray traces of those with whom society was careless in life tend to be treated carelessly in death.

In recent years, for example, there has been a realisation that the records held within the health system are a crucial repository of ordinary Irish lives. In 2006, University College Dublin and the University of Ulster got funding from the Wellcome Trust to establish the Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland. Its current research projects – on areas such as the relationship between Irish migration and mental illness, child and maternal welfare and sexual health – give a flavour of the ways in which ordinary lives can be illuminated.

Yet, even as this field of historical writing is beginning to flower, the records on which it is based are in increasing danger. The problem is simple: there is no statutory protection for the archives of medical institutions. Local county archives have usually inherited (by custom and practice) the files of the workhouses, poor law unions and health boards. (Though not all county councils actually employ a trained archivist.) Other records, however, seem to be acquired or dumped on an almost random basis.

No one has a duty to preserve them or, when appropriate, to destroy them. There are no laws to say what records should be kept, when they should be opened to scrutiny and who should have access to them.

The problem is particularly acute in one of the most important areas. It is impossible to understand the way Irish society worked up until very recently without exploring its incarceration of tens of thousands of people in prison-like mental hospitals. The mental hospitals were the third side of the Bermuda Triangle of Irish social control, alongside the industrial schools and the Magdalen homes.

Many of these institutions are now being dismantled. But there’s no coherent plan for what should happen to the archives that contain the traces of so many lost lives. National Archives staff have been trying to find homes for some of the records. The files from hospitals in Cork, Ennis and Sligo have been transferred either to county council care or to the National Archives. But the broader picture is chaotic. The HSE is not particularly interested, the National Archives have no space, and local councils may or may not have the facilities even to preserve the files, let alone arrange for proper maintenance and access. And with no legal framework, no one can make the crucial decisions about which files should be kept from scrutiny to preserve privacy and which should be available to researchers or to people tracing relatives and ancestors.

There’s a particularly bitter edge to this neglect of mental hospital records. The people who are the subjects of those records were usually locked away in order to be forgotten. Their very existence was often denied.

Their excision was part of Irish society’s construction of a version of itself that could be maintained only by relentless and often violent exclusion. And now we are continuing that process of collective denial and completing that work of obliteration.

This is just one aspect of the wider crisis in Irish archives, but it is perhaps the one that suggests most clearly what we are dealing with. We are at a moment in our history when all sorts of illusions about who we are have been stripped away by the harsh winds of economic collapse, dark revelation and the collapse of the institutional Catholic Church. We need, as never before, an honest engagement with our collective experience. The archives are the memory banks in which the traces of those experiences are stored. If we are careless with what they tell us about the past, we will construct a future of delusions."

IN MAY 2008, a woman searching for her cat near Glounthaune, outside Cork city, came across hundreds of intact files at an old landfill site. They were records from the 1970s and 1980s from St Finbarr’s and Cork University hospitals. The HSE said it had no idea how they got there. It was not the first time that dumped medical files had been found in Cork, but it was a particularly dramatic illustration of the effects of the chaos in public policy concerning archives in general and health records in particular.

Anyone with an interest in Irish history, at either a local or a national level, is probably aware of the crisis in our archives. The National Archives are almost literally full and forced to move material into unsuitable off-site storage in order to make way for the new records that have to be taken in every year. There is no coherent policy on the retention of the digital documents that now make up the bulk of official records. The Government has not bothered to re-appoint the statutory National Archives Advisory Council since the last term of office ended in November 2007 – a breach of the law that suggests a degree of outright contempt. Official policy is dominated by a hare-brained notion of merging the National Archives and the National Library.

It is easy to dismiss all of this as a matter of concern only to professional historians. It actually goes to the heart of something much larger – our collective notions of who we are. What is at stake is our ability to define our own reality. We’ve learned in the most painful way, principally from the Ryan report into the industrial school system, that the successful occlusion of some of the darkest aspects of Irish life allows us to lie about ourselves. Those lies are toxic.

One of the things that happens when the preservation of records is neglected is a strengthening of the tendency for history to be written by – or at least from the perspective of – the winners. The records of government and high diplomacy will probably survive. What get lost are the vestiges of the lives of the ordinary, the anonymous, the vulnerable. The stray traces of those with whom society was careless in life tend to be treated carelessly in death.

In recent years, for example, there has been a realisation that the records held within the health system are a crucial repository of ordinary Irish lives. In 2006, University College Dublin and the University of Ulster got funding from the Wellcome Trust to establish the Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland. Its current research projects – on areas such as the relationship between Irish migration and mental illness, child and maternal welfare and sexual health – give a flavour of the ways in which ordinary lives can be illuminated.

Yet, even as this field of historical writing is beginning to flower, the records on which it is based are in increasing danger. The problem is simple: there is no statutory protection for the archives of medical institutions. Local county archives have usually inherited (by custom and practice) the files of the workhouses, poor law unions and health boards. (Though not all county councils actually employ a trained archivist.) Other records, however, seem to be acquired or dumped on an almost random basis.

No one has a duty to preserve them or, when appropriate, to destroy them. There are no laws to say what records should be kept, when they should be opened to scrutiny and who should have access to them.

The problem is particularly acute in one of the most important areas. It is impossible to understand the way Irish society worked up until very recently without exploring its incarceration of tens of thousands of people in prison-like mental hospitals. The mental hospitals were the third side of the Bermuda Triangle of Irish social control, alongside the industrial schools and the Magdalen homes.

Many of these institutions are now being dismantled. But there’s no coherent plan for what should happen to the archives that contain the traces of so many lost lives. National Archives staff have been trying to find homes for some of the records. The files from hospitals in Cork, Ennis and Sligo have been transferred either to county council care or to the National Archives. But the broader picture is chaotic. The HSE is not particularly interested, the National Archives have no space, and local councils may or may not have the facilities even to preserve the files, let alone arrange for proper maintenance and access. And with no legal framework, no one can make the crucial decisions about which files should be kept from scrutiny to preserve privacy and which should be available to researchers or to people tracing relatives and ancestors.

There’s a particularly bitter edge to this neglect of mental hospital records. The people who are the subjects of those records were usually locked away in order to be forgotten. Their very existence was often denied.

Their excision was part of Irish society’s construction of a version of itself that could be maintained only by relentless and often violent exclusion. And now we are continuing that process of collective denial and completing that work of obliteration.

This is just one aspect of the wider crisis in Irish archives, but it is perhaps the one that suggests most clearly what we are dealing with. We are at a moment in our history when all sorts of illusions about who we are have been stripped away by the harsh winds of economic collapse, dark revelation and the collapse of the institutional Catholic Church. We need, as never before, an honest engagement with our collective experience. The archives are the memory banks in which the traces of those experiences are stored. If we are careless with what they tell us about the past, we will construct a future of delusions."

Wolf Thomas - am Sonntag, 11. April 2010, 17:34 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/apr/06/st-augustine-first-edition-auction

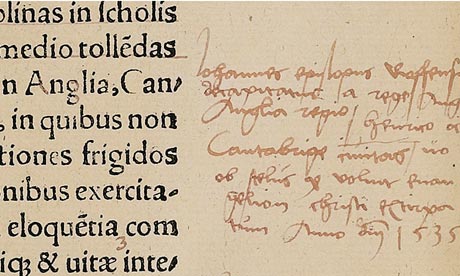

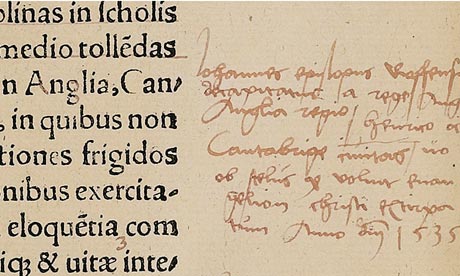

A meticulously annotated 10-volume edition of the works of St Augustine, offering new insights into one of the most turbulent times in English religious history – Henry VIII's break with Rome – is to be auctioned.

Sotheby's has announced it is to sell an extremely rare and perfectly conditioned first edition of St Augustine's complete works as edited by Erasmus. What makes the set of books even more special is the thousands of tiny red-ink corrections, amendments and commentaries, the majority of which have not been studied academically. [...]

In total, more than 8,000 pages have been annotated with remarks including more than 400 important doctrinal commentaries – from 50 to 3,000 words – by Luther and his fellow reformers, such as Philipp Melanchthon, Wenzeslaus Linck and George Spalatin.

A meticulously annotated 10-volume edition of the works of St Augustine, offering new insights into one of the most turbulent times in English religious history – Henry VIII's break with Rome – is to be auctioned.

Sotheby's has announced it is to sell an extremely rare and perfectly conditioned first edition of St Augustine's complete works as edited by Erasmus. What makes the set of books even more special is the thousands of tiny red-ink corrections, amendments and commentaries, the majority of which have not been studied academically. [...]

In total, more than 8,000 pages have been annotated with remarks including more than 400 important doctrinal commentaries – from 50 to 3,000 words – by Luther and his fellow reformers, such as Philipp Melanchthon, Wenzeslaus Linck and George Spalatin.

KlausGraf - am Sonntag, 11. April 2010, 16:16 - Rubrik: English Corner

http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?sectioncode=26&storycode=411112&c=1

Excerpt:

Ms Peters recalled: "We were worried it would be auctioned off and dispersed, so we worked hard to keep it together and within Wales."

The university put £500,000 towards the cost of buying the collection, with further funding from Cardiff Council, the Welsh Assembly government, Museums Archives and Libraries Wales and the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales.

The university's special collection had hitherto consisted mainly of works purchased in the 19th century, and either written in Welsh or dealing with Wales.

That collection has now been dramatically enhanced, with books from across Europe dealing with pretty much everything under the sun.

With its new acquisition, Cardiff's holding of incunabula (early printed books) has risen from zero to 175, putting it among the top 10 collections in Britain. There is also a significant travel section, with 250 rare atlases and a signed copy of Ernest Shackleton's account of his journey to Antarctica.

Its material on Restoration drama and its 17th- and 18th-century editions of Shakespeare are as comprehensive as anywhere in Britain apart from the British Library and the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. Bibles, herbals and limited-edition books printed by private presses of the late 19th and early 20th century are also well represented.

All these will be housed within the Arts and Social Studies Library and will be available to the general public, with plans to digitise many of the more important volumes.

Ms Peters said the acquisition means that the university's collection is likely to be the largest collection of early non-Welsh material in Wales.

See here

http://archiv.twoday.net/search?q=cardiff

Excerpt:

Ms Peters recalled: "We were worried it would be auctioned off and dispersed, so we worked hard to keep it together and within Wales."

The university put £500,000 towards the cost of buying the collection, with further funding from Cardiff Council, the Welsh Assembly government, Museums Archives and Libraries Wales and the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales.

The university's special collection had hitherto consisted mainly of works purchased in the 19th century, and either written in Welsh or dealing with Wales.

That collection has now been dramatically enhanced, with books from across Europe dealing with pretty much everything under the sun.

With its new acquisition, Cardiff's holding of incunabula (early printed books) has risen from zero to 175, putting it among the top 10 collections in Britain. There is also a significant travel section, with 250 rare atlases and a signed copy of Ernest Shackleton's account of his journey to Antarctica.

Its material on Restoration drama and its 17th- and 18th-century editions of Shakespeare are as comprehensive as anywhere in Britain apart from the British Library and the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. Bibles, herbals and limited-edition books printed by private presses of the late 19th and early 20th century are also well represented.

All these will be housed within the Arts and Social Studies Library and will be available to the general public, with plans to digitise many of the more important volumes.

Ms Peters said the acquisition means that the university's collection is likely to be the largest collection of early non-Welsh material in Wales.

See here

http://archiv.twoday.net/search?q=cardiff

KlausGraf - am Samstag, 10. April 2010, 17:11 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen

April 12 to April 24 2010

@ Home Works

Ashkal Alwan

Beirut

To not wait for the archive is often a practical response to the fact that there are missing or absent archives in many parts of the world. And to wait for the state archive, or to wait to be archived, is not a healthy option. Archiving practices-- finding and caring for things, drawing on existing collections, publishing from archives-- are then political practices, which in different ways overwrite their own futures. By now, digital technologies and its networks are fully enmeshed in these questions of the archive and the future: with "archivisation" and auto-archiving on the one hand, and the continuing anxieties and possibilities around reproduction and distribution, on the other.

So is there something, in the density of our contemporary experiences in Bombay, Bangalore, Beirut or on the internet, that can lead us to a shared theory of the archive that goes beyond its dominant canons (Benjamin, Foucault, Derrida)?

The realist metaphysics of "don't wait" lets us see the archive as neither a fixed concept nor as unbounded potential, but as a concrete set of negotiations, costs, transactions, tools and imaginations that hold an archive together, and that may be further "traded". To begin this kind of trafficking: in open software, in films and footage, in interests and curiosities, in histories and objects, in articulations of the regional and universal future of images-- is the reason we come to Beirut and to Home Works.

The project is proposed as a two-week workshop period, more a time for production than an extended "event". The workshop will involve working with materials from Beirut (the Cinemayat video collection from 2006 is one starting point) which will be digitised and annotated through pad.ma. Further, filmmakers, writers and researchers are invited to contribute materials, and to explore ways of writing across and through video material. During Home Works, the pad.ma group and the Beirut participants will take part in a 5-hour colloquium, which will present and discuss our findings.

24 April, Saturday http://pad.ma Colloquim at Home Works V, 4:30 pm - 9:30 pm.

Link

@ Home Works

Ashkal Alwan

Beirut

To not wait for the archive is often a practical response to the fact that there are missing or absent archives in many parts of the world. And to wait for the state archive, or to wait to be archived, is not a healthy option. Archiving practices-- finding and caring for things, drawing on existing collections, publishing from archives-- are then political practices, which in different ways overwrite their own futures. By now, digital technologies and its networks are fully enmeshed in these questions of the archive and the future: with "archivisation" and auto-archiving on the one hand, and the continuing anxieties and possibilities around reproduction and distribution, on the other.

So is there something, in the density of our contemporary experiences in Bombay, Bangalore, Beirut or on the internet, that can lead us to a shared theory of the archive that goes beyond its dominant canons (Benjamin, Foucault, Derrida)?

The realist metaphysics of "don't wait" lets us see the archive as neither a fixed concept nor as unbounded potential, but as a concrete set of negotiations, costs, transactions, tools and imaginations that hold an archive together, and that may be further "traded". To begin this kind of trafficking: in open software, in films and footage, in interests and curiosities, in histories and objects, in articulations of the regional and universal future of images-- is the reason we come to Beirut and to Home Works.

The project is proposed as a two-week workshop period, more a time for production than an extended "event". The workshop will involve working with materials from Beirut (the Cinemayat video collection from 2006 is one starting point) which will be digitised and annotated through pad.ma. Further, filmmakers, writers and researchers are invited to contribute materials, and to explore ways of writing across and through video material. During Home Works, the pad.ma group and the Beirut participants will take part in a 5-hour colloquium, which will present and discuss our findings.

24 April, Saturday http://pad.ma Colloquim at Home Works V, 4:30 pm - 9:30 pm.

Link

Wolf Thomas - am Mittwoch, 7. April 2010, 22:11 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen

KlausGraf - am Mittwoch, 7. April 2010, 05:11 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen

KlausGraf - am Dienstag, 6. April 2010, 15:34 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen

KlausGraf - am Montag, 5. April 2010, 23:36 - Rubrik: English Corner

noch kein Kommentar - Kommentar verfassen